Whitsunday Islands

AS MY PADDLE BREAKS the bay’s glassy surface, I see a shadow dart beneath my kayak. Its shape gives it away as a turtle, possibly the green turtle that surfaced beside me a few minutes ago, opening its beak-like mouth for air before darting into the deep. Today I’ve seen many turtles gliding through the waters off Crayfish Beach, a stunning stretch of sand, rock and coral on the north-east of Hook Island, part of Queensland’s Whitsunday archipelago. I’ve also passed over schools of fish negotiating the maze of mangrove roots lining the inlet to the north of my campsite, and been joined for a short time by a humpback whale. An earlier snorkel over Mackerel Bay’s fringing coral reefs introduced me to a 1 m long humphead Maori wrasse, an exquisitely coloured beaked coralfish, a delicate threadfin butterflyfish, and the seemingly infinite colours and textures of tube and staghorn corals.

It’s only 24 hours since the almost concave cliffs of the bay were battered by strong winds and large seas – and Scamper, the landing craft that brought me here, was pitching and rolling over waves of increasing size and ferocity. We were on our way from the relative calm of the mainland’s Shute Harbour when what started as seaspray whipping over the sides turned, in a heartbeat, into sheets of water hitting the deck. Our skipper, Neill Kennedy, hollered down from the bridge, “I’m sure you guys want to live…so we have to turn around.”

It wasn’t long before we were grinding up onto the pebbly shores of Sandy Bay on South Molle Island, one of more than 90 isles in the Whitsundays region. Just a few hours later I was standing on the top of Mt Jeffreys, the highest point of South Molle, gazing at islands rising from the sapphire sea. Stands of hoop pines cling to windswept hillsides in the south; eucalypt woodlands slope down towards gullies lined with vine thickets and casuarinas to the north. Hundreds of grass trees cover the ridges like the spears of a great army. A brahminy kite was riding the wind still shrieking over the island’s peaks, while a couple of sooty oystercatchers searched for molluscs in the rock pools. I was in a true island paradise – its very essence formed by the competing forces of sun, sea, wind and rain. The kind of place in which you feel simultaneously at the mercy of, and indebted to, nature.

Whitsunday’s treasure islands

The Whitsunday group is one of the largest offshore island chains in the country, but it was once part of the mainland. Each island is a peak in a mountain range that was flooded about 10,000 years ago, as sea levels rose by 100 m at the end of the most recent ice age. In June 1770, British navigator James Cook became the first European to make a record of the islands. Cook named them the Cumberland Isles, and dubbed the stretch of water between Cape Conway and the islands to the east Whitsunday’s Passage. Surveyors and hydrographers later named and arranged the islands into the Lindeman, Sir James Smith and Whitsunday groups, as well as Anchor and Repulse islands. David Colfelt, author of the authoritative 100 Magic Miles of the Great Barrier Reef, notes that while “there are some 150 islands, islets and rocks in the Cumberlands… Someone somewhere along the line in an advertising brochure seized upon the number ‘74’ as being the number of ‘Whitsunday islands’, a figure often touted in promotion of the area but which has no rational basis.”

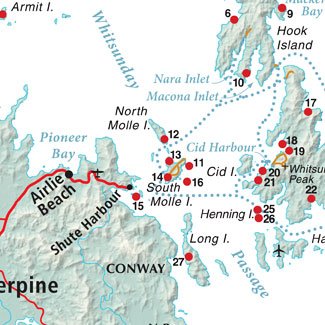

Camping hot spots View Large Map

The islands in the Whitsunday Group are many things to many people. Offering a mix of accommodation styles, and with scuba-diving tours, reef excursions and boating trips making up most of its tourism fabric, you might be tempted to write off the region – one of Australia’s most popular tourist destinations – as overexploited. But this picture-postcard stretch of the Great Barrier Reef features a host of uninhabited islands offering many intimate campsites with tight restrictions on camper numbers.

Most of the islands are designated national parks, and the campsites are run by the Queensland Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Sites dot the smaller islands closer to the mainland: North and South Molle, Denman, Long, Tancred and Planton – the latter proving to be a wonderful place to camp. Resident bush stone-curlews regale me with eerie calls as I feast on oysters prised from rocks in the intertidal zone, an EPA-approved culinary experience in this section of the Whitsundays.

Further east, the two largest islands in the archipelago – Hook and Whitsunday – contain most of the region’s camping. While the diversity of coral at sites such as Maureens Cove, Steen’s Beach and Crayfish Beach is a huge drawcard, Hook Island is also renowned for its scuba diving and snorkelling as well as abundant wildlife – from white-bellied sea eagles patrolling the skies to lace monitors and bush turkeys roaming the land. It also features thick banks of mangroves – so vital to the area’s marine life – and inviting stretches of cool rainforest. I share the Crayfish Beach campsite with French siblings Vincent and Natalie Pertue, and Natalie’s boyfriend Christophe Brenner. Vincent’s enthusiasm for the beauty of their surrounds is infectious. “It’s an amazing adventure, being dropped off on a wild island like this,” he says. “Camping here with a great view from your tent when you wake up in the morning. Then you pick up your kayak at sunrise and skate smoothly over the clear and quiet turquoise water. It’s magic.”

Another soul-soothing spot is undoubtedly the jewel in Whitsunday Island’s crown: Whitehaven Beach – the most popular and recognisable site in the region, courtesy of its 5 km long stretch of white, silica-rich sand. This east-coast drawcard is extremely popular with daytrippers, but once they’ve left you have it all to yourself. Whitsunday Island’s west coast is also stunning. Dugong Beach is connected by a rainforest-lined 1 km walking track to Sawmill Beach, home to a seasonal freshwater creek. You can also camp on the southern islands of Lindeman, Shaw, South Repulse and Newry, as well as Whitsunday Island’s petite western neighbour, Henning Island. Some camping grounds cater for larger groups – 36 people at Dugong, 60 at Whitehaven – while others, such as Turtle Bay, accommodate 12. Only four people are allowed to camp on Denman and Planton islands at a time, which I’m sure is just how the curlews like it.

Whitsunday trails: Walk on the isle side

Interesting walks have always been part of the area, but the Whitsunday Ngaro Sea Trail, currently under development by the EPA, will offer new and improved tracks of varying difficulty on Hook, Whitsunday and South Molle islands. Part of the Great Walks of Queensland initiative (AG 86), the trail is designed to follow the paths of the Ngaro people, the traditional owners of the region and one of the earliest recorded Aboriginal groups in Australia. By private vessel, charter boat or kayak, walkers will be able to travel between the three islands, linking up with walking tracks that pass Ngaro art and cultural sites.

When I meet EPA indigenous liaison ranger Bryan Phillips he is putting the finishing touches to the upgraded camping ground at Whitehaven Beach, but is happy to have a chat in the shade of the tea-trees and she-oaks that line this famous stretch of sand. He explains that while the Whitsundays region has been inhabited for thousands of years, many of the older sites of cultural significance are now under water. “But there’s a well-known quarry on South Molle Island that is on the sea trail,” he says. “[University of Southern Queensland researchers] Bryce Barker and Lara Lamb did a fair bit of work up there, and they indicated that it’s at least 9000 years old and is probably the most significant in Queensland. You can see little bits of splintered rock, and that’s the actual rocks that were used to make knives.”

Bryan says that the Ngaro developed a distinctive art style that can still be seen in paintings on the sea trail. “In fact, the whole southern end of Hook Island is littered with caves and sites, all around Macona and Nara inlets,” he says. “Nara probably has eight or nine caves with paintings and artefacts.” I ask him whether there were ever any permanent settlements on the islands. “The most prominent indigenous campsite was Cid Harbour on Whitsunday Island, which was used as a campsite all year round,” he says. Analysis of middens in this region have revealed that fish, crabs, turtles, shellfish, marsupials, reptiles and birds were all part of the traditional diet, along with many edible plants.

Whitsunday Islands: Love at first site

As the days roll on, each sunnier and calmer than the one before, Scamper ferries me from one campsite to the next. I spend my time kayaking, snorkelling, walking and exploring, not to mention enjoying the sun and the sea breeze. I feel like a castaway, camping on the edge of the world. This is never stronger than on my last night in the Whitsundays, which coincides with a new moon. I sit on a strip of sand in near total darkness, the sky above me resembling the grandest of pincushions.

I think of the chat I had a few days earlier with local EPA spokesman Michael Phelan, who revealed: “I’ve travelled far and wide, but nowhere else has captured my imagination. I lived in the Whitsundays in the late 1990s. Before returning last year, I spent those 10 years daydreaming about coming back.”

It’s clear to me now, as I sit on this beach under the stars, that I’ve fallen under the same spell. I can’t say it better than he did: “I simply fell in love with the place. Sounds like a cliché but it’s the truth. This place does that to you.”

Source: Australian Geographic (Oct – Dec 2008)

RELATED STORIES