Pat Edmondson sits near a campfire that smokes half-heartedly in the mild autumn air. His son Mike brings the 94-year-old a cup of tea from the billy. Behind them stands a wooden hut, simple in construction yet strong against the elements that are thrown its way year-round.

The blue-grey and rusted-brown of the hut’s corrugated iron A-frame roof contrasts with the green of the surrounding grasses. Golden morning light splays across its weatherboard walls. Whatever the weather in this southern end of Kosciuszko National Park, in New South Wales, Cascade Hut (known as Cascades) is a welcome sight.

“It was on a bit of a lean,” Pat recalls of the first time, in 1969, that he saw Cascades. After hearing about it from a friend, he and his wife, Sue, had spent the day searching for it on a cross-country ski trip with their three young children in tow. “The ground and the hut were covered with snow,” Pat says. “We were relieved that we’d found it…there were no snow tents back then and maps weren’t quite what they are now.”

After 50 years of visiting Cascades (“perhaps 200 times”, he guesses), Pat has seen the hut – and the open frost hollow adjoining it, where it’s too cold for trees to grow – in all kinds of weather. “On a windy day you can see patterns in the trees as you look across the secluded valley,” he says. “The treetops move in waves and the light is amazing.”

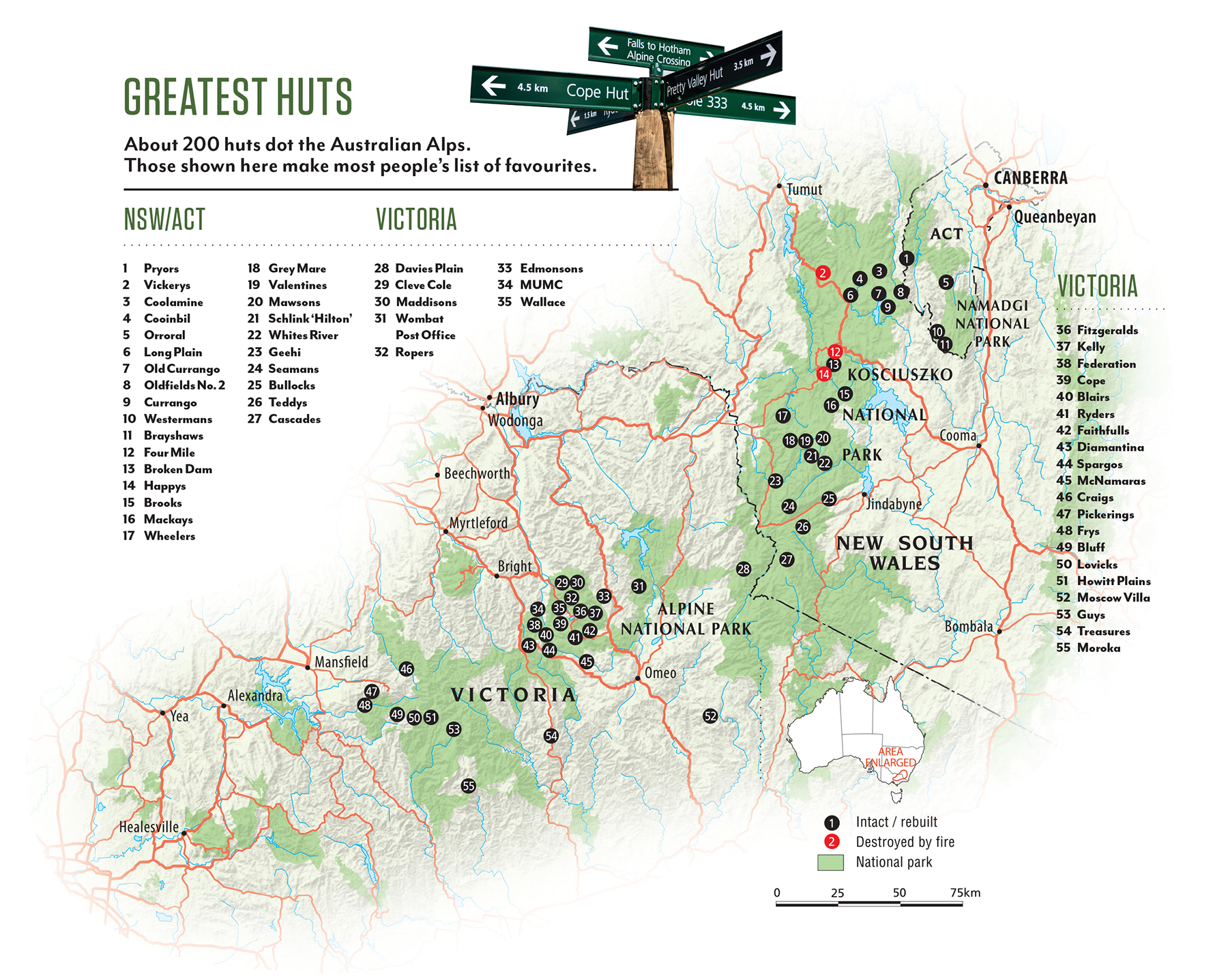

Alpine huts hold a special place in the national psyche, epitomising ideals about what it means to be Australian: hardy, resourceful and rugged. There are about 200 dotted across the Australian Alps, built by graziers, goldminers, foresters, Snowy Mountains Scheme workers, skiers and bushwalkers – some as early as the 1860s. Today, a handful of devoted volunteer groups keeps them standing.

Pat worked as an engineer for 30 years in Wollongong, south of Sydney, before moving to Jindabyne, on the edge of the NSW Snowy Mountains, in 1985. Described by fellow volunteers and friends as “a quiet achiever…team leader, technical expert, and passionate historian”, he’s been a key player in protecting and maintaining the huts.

He’s been a long-time member of the Illawarra Alpine Club (IAC), and with a team of fellow volunteers from the club took on the role of caretaker for Cascades and, later, three other nearby huts – Charlie Carters, Tin Mines and Teddys.

Cascades was built in 1935 by Rob Benson for the Nankervis family as a refuge for cattlemen needing shelter while herding stock or “brumby running”. These days, skiers, bushwalkers and mountain-bike riders are the most common visitors.

Inside, there’s a box of matches and stack of dry firewood. Visitors are expected to follow an unspoken etiquette that involves them using the hut for refuge; only overnighting in emergency situations; treating it with respect; replacing what they use; and taking care with fires and candles. “Whatever you do,” says Pat, “don’t set fire to it. That’s rule number one.”

Pat has many happy memories of being at Cascades. He recalls erecting tents nearby with Sue and their children, lighting the fire inside, closing the door against the snow during the annual ski tours he shared with friends for 20 years, and passing around rum toddies with fellow volunteers during working bees.

Pat and Sue have passed on their love of adventure, nature and the mountains to their children. Their eldest son, Mike, spends much of the year in a tent under the star-filled sky teaching clients nature photography and bush skills, helping them to be self-sufficient in the bush, even when it’s under a blanket of snow (see Mike’s photo on our cover). Mike knows the value Cascades holds for Pat. “He gets joy in watching other people coming out here and experiencing the park,” Mike says. “He has a deep love for this area, so it’s a way of giving back.”

Pat appreciates the experiences Cascades has given him in this valley flanked by alpine grasses, heaths and wildflowers, and surrounded by snow- and mountain-gum forests. The hut remains standing today in large part due to his efforts, along with those of Sue, fellow IAC volunteers and other members of the Kosciuszko Huts Association (KHA). The work of volunteers is invaluable to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), which has ultimate responsibility for the huts.

Every year since 1975, a group of IAC volunteers has gathered each Easter to maintain Cascades. In 1975 the challenge was immense. The hut was 40 years old but “looked much older”, according to Pat. The rammed earth floor needed upgrading, the structural posts needed replacing, drainage around the hut required attention and the bark roof leaked. The challenge was not simply to improve the hut’s function, but also to restore the heritage building’s original aesthetics. Pat and the NPWS were guided by the Burra Charter, which, published in 1979, outlines the principles and procedures that should be adhered to when conserving heritage places in Australia.

Former NPWS regional manager Dave Darlington, who’s become a good friend of Pat and his family, says most visitors wouldn’t realise the dedication that’s gone into preserving the function and original aesthetics of Cascades. “You wouldn’t realise that it’s got new bones inside it, not unlike a human getting a couple of artificial joint replacements,” he says. “It looks the same on the outside, but the inside is super strong and it withstands the elements.”

Fellow volunteer and Pat’s long-time friend Col Wooden agrees. “You can’t just get a carpenter to come and rebuild these huts,” he says, “because you’ll end up with a box. You’ve got to teach them to be bodgy.”

The “bodginess” Col refers to includes creative ways of upholding a historic appearance while improving the hut’s durability in alpine conditions. According to Col, Pat was meticulous about using original materials and traditional techniques but occasionally stuck to his guns when he considered function to be more important.

Dave cites three elements that come together when preserving the cultural heritage of huts. “First, you need to understand the historical context of the huts,” he says. “Then you need to have the technique or knowledge to replace a roof, a chimney, or a post that’s rotted out, and third, you need to be able to manage a team of people.” Added to this is the challenge of working in a remote location, where tools, materials and equipment sometimes need to be carried in on foot. “You’re not in a place where you can bring up a scissor lift, press a button and the lift goes up in the air,” Dave says. “You’re in the middle of nowhere.”

Dave worked with many volunteer groups during his time with the NPWS. “Volunteer groups are the lifeline for these huts,” he says. “And this group is one of the best I’ve ever interacted with. They’re capable, they’re passionate, and they’ve had that long-term connection with the huts they’re maintaining.”

The passion of people for alpine huts is never more evident than when those huts are threatened by bushfires. In the 2019–20 Black Summer, 12 Snowy Mountains huts were lost despite considerable efforts of firefighters. Thanks to some creative thinking from Dave and his team, who came up with the idea of wrapping huts in a type of foil to protect them from fire and embers, Cascades still stands, strong, tall and unburnt by those devastating fires. The technique has since saved many other huts.

Lachie Gales places an unusual-looking axe into his backpack and shoulders the load. The tool – a broadaxe – looks like something from a Game of Thrones’ set. It was made 100 years ago and used by bush carpenters whose trade now is as rare as the axe itself. “Occasionally you come across workmanship in a hut that was built by cattlemen,” Lachie says. “And you can tell a skilled bush carpenter has been there.”

Because of its wide cutting edge and bevelling (sharpening) on only one side, the broadaxe is used by carpenters to make flat surfaces from round logs. The axe helps Lachie and his team retain the original features of the huts they restore.

Lachie and his mate Pat O’Donohue follow snow poles that have been strategically placed to mark a route across the Bogong High Plains, in the Victorian Alps, towards Mt Jim and Mt Cope. Pat, whose red Gore-Tex jacket stands out against the dreary sky, is carrying a ladder. As the clouds part briefly, Westons Hut comes into view.

The long-term nature of Lachie and Pat’s friendship is evident in their banter. Their deep connection with Australia’s High Country began years ago. For Lachie, it was through a high school economics teacher who had a passion for adventure and encouraged him to experience the mountains. “That teacher created a turning-point moment in my life,” says Lachie, who responded well to the physical challenges of being in the bush, and the need for self-reliance it engendered.

Lachie maintains his love of the bush 45 years later by restoring and maintaining huts in far-flung places. His work with Pat and other volunteers is a way of giving others access to nature. “Our group’s passion for these huts is seeded in our respect for this place,” Pat says. “It started as a way to contribute back, but now it’s become something bigger than that.”

In 2010 Pat and Lachie were among two dozen volunteers who resurrected Westons Hut, surrounded by the charred trunks of snow gums and mountain ash trees that burnt with the original building in the 2006–07 fires. Many huts lost to fires aren’t rebuilt. Westons had a different fate, for two reasons. First was its value to the Weston family. With links to cattlemen Eric Weston and Fred Briggs, who built the hut in 1932, the family advocated strongly

for its resurrection, partly because of its ideal location midway between Mt Feathertop and the Bogong High Plains. Second, it survived thanks to the hard work and commitment of a team of volunteers from the Victorian High Country Huts Association, led by Lachie. With a quiet but upbeat leadership style, and a wealth of skills gained running a building business in Wangaratta for 35 years, he was the driving force behind the restoration.

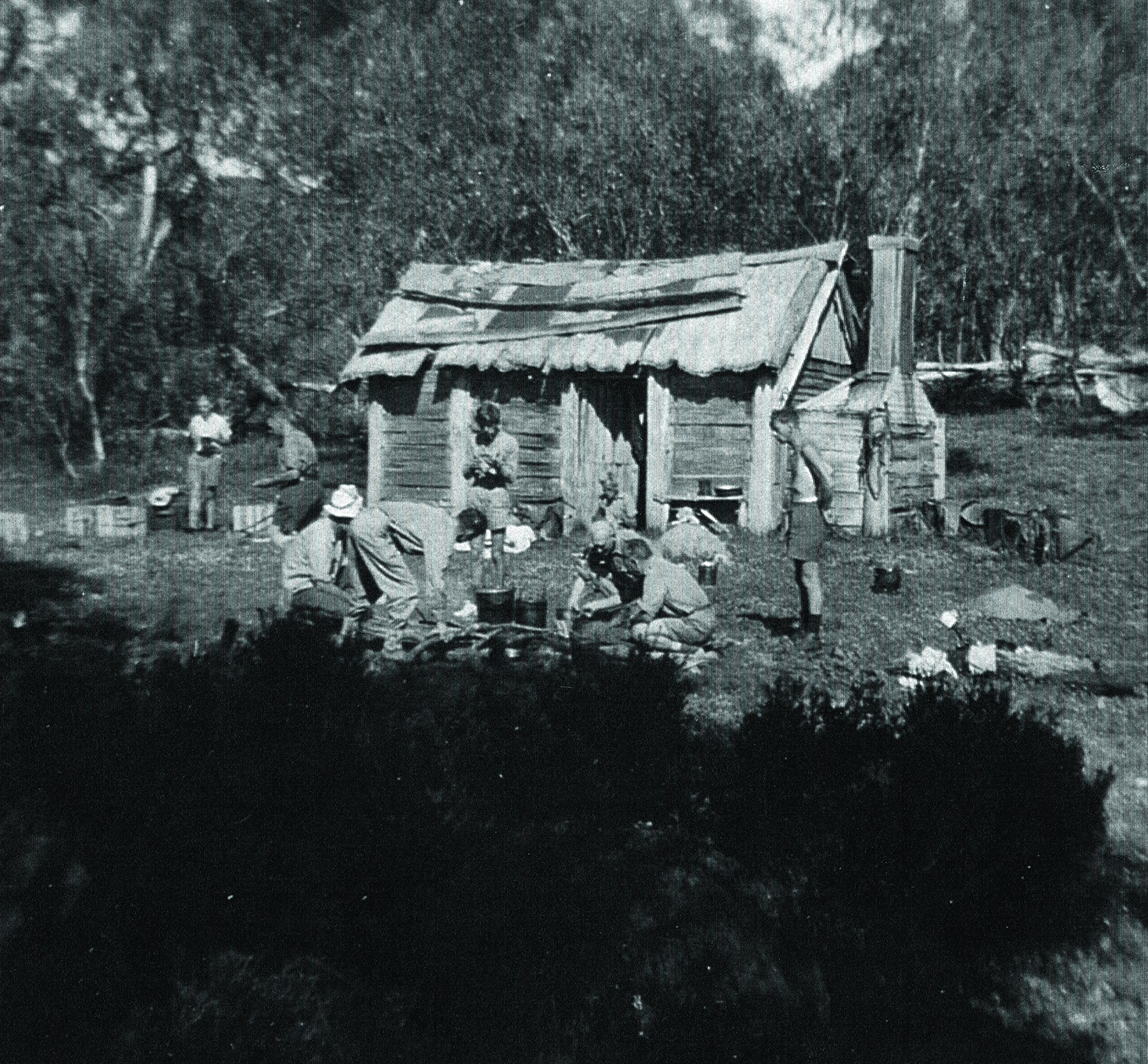

Lachie admires the resourcefulness of the cattlemen who built the huts: they did what they could with what they could find, working with the timber harvested nearby using materials they could repurpose, including kerosene cans flattened into tin sheets.

Stepping into the huts transports Lachie to those times, and he feels humbled. “I have a deep understanding of what it takes to build any sort of structure – the physicality, the mental effort, and the resilience required,” he says. “For the old-timers, those issues were much more difficult, and every time I see their work, I’m transported back in empathy to what they endured. I sit at the feet of those who came before.”

Yet as a qualified builder he can’t resist improving on the workmanship where he can. “The romanticism of cattlemen’s huts doesn’t travel very far with us,” Lachie says, laughing. “Cattlemen had determination and grit, but they weren’t always great builders.” He refers to leaky bark roofs, chimneys on a lean and crumbling stone structures that were never intended to withstand decades of exposure to harsh sunshine and pelting rain. In bringing Westons back to life, Lachie and his team paid homage to the original design. The existing post holes defined the shape of the new building and the split palings that now clad the walls were made in the traditional way. The high, pitched roof and sheltered verandah reflect what was there before.

“Our brief was to build a functional refuge that had a clear connection to the previous heritage of the original hut,” Lachie says. Built using a combination of traditional and contemporary methods, Westons will endure the alpine weather for years to come.

Ten or so kilometres east of Westons, a small group of bushwalkers shelters from the rain inside Cope Hut. Sleeping bags hang from the rafters, drying in the heat of a pot-belly fire. When I open the door, I instantly feel the warmth from inside – the insulation Lachie and Pat’s team installed five years ago is working its magic.

A woman warming by the fire with a hot cup of tea is immensely grateful for the refuge of the hut. She and her partner arrived with wet boots, packs and sleeping bags. “It’s so good to be dry and warm in here,” she says. “It’s a welcome solace from a day in the rain.”

The woman is enjoying the hut in exactly the way Lachie, Pat and the Cascades crew envisaged. An alpine hut is a place of safety, a refuge from the wilds, and a way to make the mountains accessible to those who dare to wander from the security of their everyday lives. After hours of physical exertion and the mental load that adventure can sometimes bring, the huts are there to provide shelter and solace.

“You just throw your pack off,” Pat says “You get your choofer [fuel stove] out and warm something. You feel the burden falling away from you and sheer relief just to be there. It’s just beautiful.”

When Kelly Searl arrived as a child in the Snowy Mountains for family ski trips to find Kosciuszko without snow, her parents would take her into the back country, where they’d walk to a hut. “You’d have to cross rivers and take your shoes off, put them back on, jump on your parents’ backs. I remember it just being so much fun as a kid,” she says.

Years later, Kelly still returns to the mountains and enjoys the same kinds of experiences in the alpine huts with her own kids. “You always come in with rosy cheeks and a cold nose, but lungs full of mountain air, so you never feel anything but excellent,” she says. “Or you’re wet, but it’s still fun because you get a hot chocolate once you get to the hut.”

In 2020 Kelly was moved by the horror of watching thousands of hectares of the Australian Alps burn in the Black Summer bushfires. After building a successful sustainable homewares company, Pony Rider, she wanted to give something back. She created The National Project, a not-for-profit initiative that is raising funds to restore Bullocks Hut, in Kosciuszko NP, via customer donations and a percentage of sales.

“The absolute premise of what I believe is that to change someone’s nature, they need to experience nature,” Kelly says. “But how can people get out there among it if there’s no safe space or shelter?”

While Kelly has never met Pat Edmondson and his son Mike, nor Lachie Gales and his long-time friend Pat O’Donohue, Kelly is grateful to the people who have devoted so much of their lives to caring for alpine huts.

“I’m in awe of them,” she says. She sees the solution to many of the world’s ills as getting people out into nature – and the huts are a vehicle to that solution. “A hut is something that’s been handmade by somebody. It’s been made for a purpose. It’s not made for vanity. It’s made for shelter, just like a home is.”

Alpine huts and the ethos around them provide opportunities for connection and grounding that Kelly believes people seek. “I think everybody is struggling for more connection, especially in this digital world. So I love the hut ethos, which says you always leave something for the next person. You always make sure there’s a packet of matches, and there’s firewood inside that’s dry,” she says. “If we applied the leave-it-better-than-you-found-it hut ethos to our planet, this earth would be such a better place.”